“Ten Questions for Devon Walker-Figueroa,” Poets & Writers

“One of the book’s final poems, “My Invention,” offers an apt metaphor for the Promethean daring of this second collection: In darkness, the poet sees herself carrying “my tune like a torch,” one held aloft even after the moths have lost interest. Walker-Figueroa suggests that such “shifty mechanisms” of light have enraptured poets and scientists in a shared project of collapsing time and distance. “My Invention” ranges from Li Bai holding a “dynasty of moonlight” to Nikola Tesla’s dream of a mechanical eye that will see all the world at once, the Earth being the “first poem it will commit / to memory.” Here and throughout Lazarus Species, Walker-Figueroa invites her readers to “See filament give way / To lament,” illuminating the proximity of invention and extinguishment, scientific discovery and poetic enchantment, an unstable past and a future eclipsed by climate change.” —Evangeline Riddiford Graham

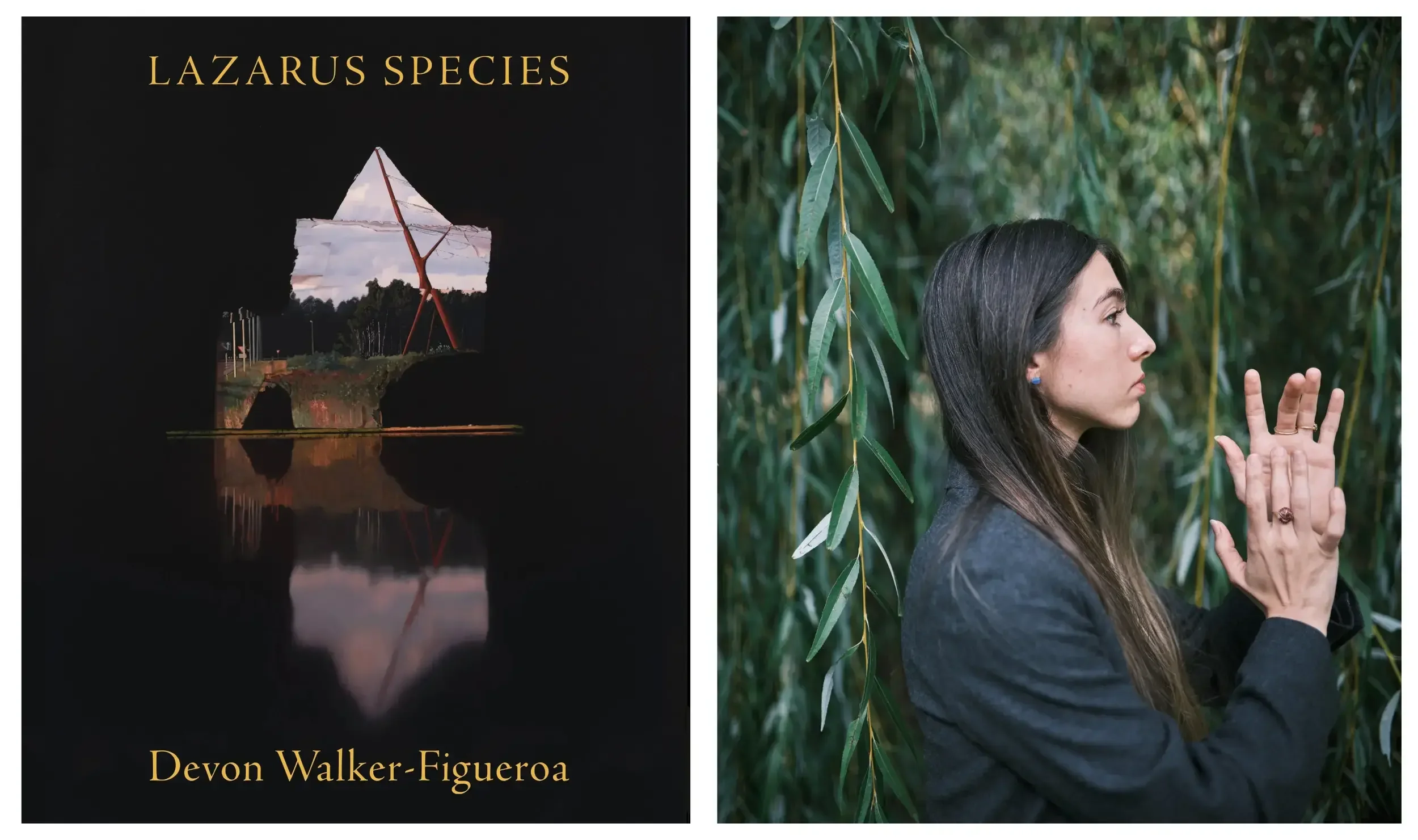

“I know few compliments in contemporary poetry criticism quite as ubiquitous as breathlessly telling a poet no one else could write what you write. Ultimately, there’s no compliment quite as hollow: just because no one else could write what you write doesn’t mean that you should write that way either. So it’s a rare surprise when the compliment carries real weight, when a poem appears that’s at once the inimitable product of an idiosyncratic mind and a public good for poetry generally. Reading Devon Walker-Figueroa’s second collection Lazarus Species, I felt that surprise in poem after poem; you might feel it simply from hearing about it.

No one but Walker-Figueroa would explore the long history of stargazing by rewriting Sir Philip Sidney’s sonnet sequence Astrophil and Stella as “Australopitheca & Starman,” in which the Australopithecus afarensis fossil commonly nicknamed “Lucy” addresses the mannequin known as Starman, who’s currently orbiting the sun in Elon Musk’s Tesla Roadster. No one but Walker-Figueroa would take the recent vogue for the sestina, a form that obsessively repeats the same six end-words, to its mind-numbing conclusion by writing a super-sized, seven-end-word variation called “The Euthanasia Coaster,” inspired by a hypothetical roller coaster that loop-de-loops its passengers into “euthanasia- / induced euphoria.” Walker-Figueroa’s excesses at every scale—her phoneme-braiding lines, her conceits stacked on conceits, this extravagantly long collection—mirror the intricacies she finds abundantly in natural biodiversity and human ingenuity. They’re also defense mechanisms in an inhospitable world, as in Walker-Figueroa’s title poem, named after species that return to life after apparent extinction: “You don’t even need to be born / again in order to be born against / this riddled wall, each bayonet in love / with your bare, stigmatic neck.” —Christopher Spaide, Literary Hub

“Noise Cancelling”

Read by Maggie Smith

“Formally inventive, the poems feature extensive footnotes, which are disrupted by striking confessional moments: “You find your family,/ your whole phyla & future, buried/ in some encyclopedia & glean/ how small the risk of eternity.” No two entries are alike, cycling from classical forms to modern text-speak, from Mars to a restaurant in Brooklyn. Despite the crises looming in the background, Walker-Figueroa writes with wit and defiance: “Why not gallop to our end? Press/ Send & kiss gravity hello?” The result is gripping and idiosyncratic.”

“Devon Walker-Figueroa’s latest poetry collection Lazarus Species serves up an ambitious body of work sizzling with unique connections delivered at the speed of synaptic firing. Where else could you hope to find a prehistoric and futuristic reimagining of Sir Philip Sydney’s Petrarchan sonnet series “Astrophil and Stella”; footnote-layered deep dives into figures such as Jack Dempsey, Lawrence of Arabia, and Nikola Tesla; and layered examinations on speaking in tongues, sensual snails, arsenic-tinged serial killers, mathematic problems, or awkward business dinners? These intersections are only part of the reason that Lazarus Species might be best described as a museum-archive-meets-mycellium-network. With Walker-Figueroa’s erudite and unabashed sensibility, each subject and sonic phrase becomes a link for a myriad of allusions, associations, admissions, and astonishments.

The sprawling scope of Lazarus Species is tethered by the intimacy of its internal logic. Whether a poem is mapped along tributaries of traditional forms, driven by sonic qualities, shaped by theorems, or guided by the mental mechanisms of the speaker, a conscious intricacy is palpable throughout the collection.”

—Claire Jussel, “On a Planet’s Calando Applause”: Diction, Decay, and Deep Dives in Devon Walker Figueroa’s Lazarus Species,” West Trade Review

Multi-Verse Podcast, Episode 16, interviewed by Evangeline Riddiford Graham about “Private Lessons,” originally published in Best New Poets 2019

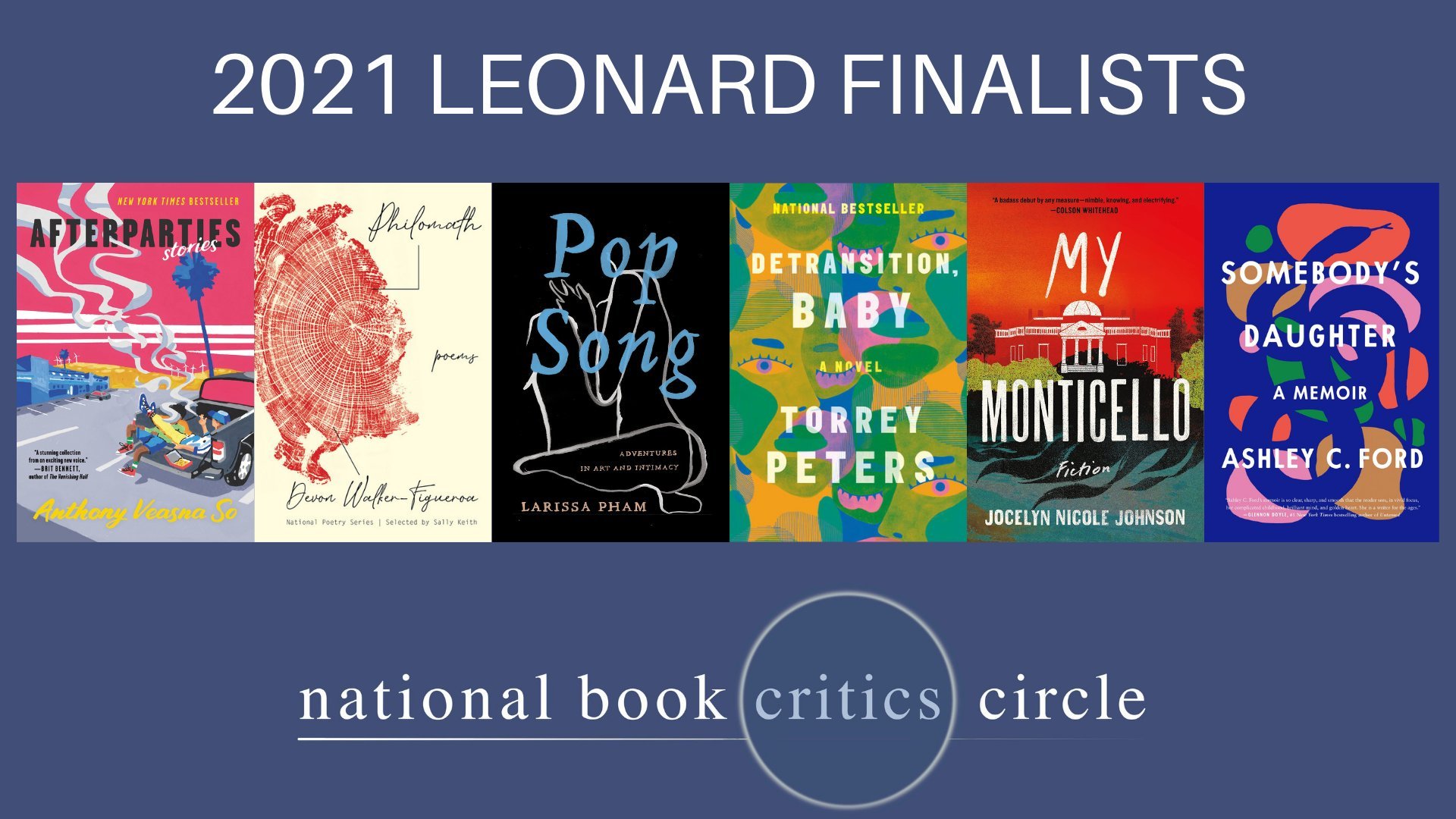

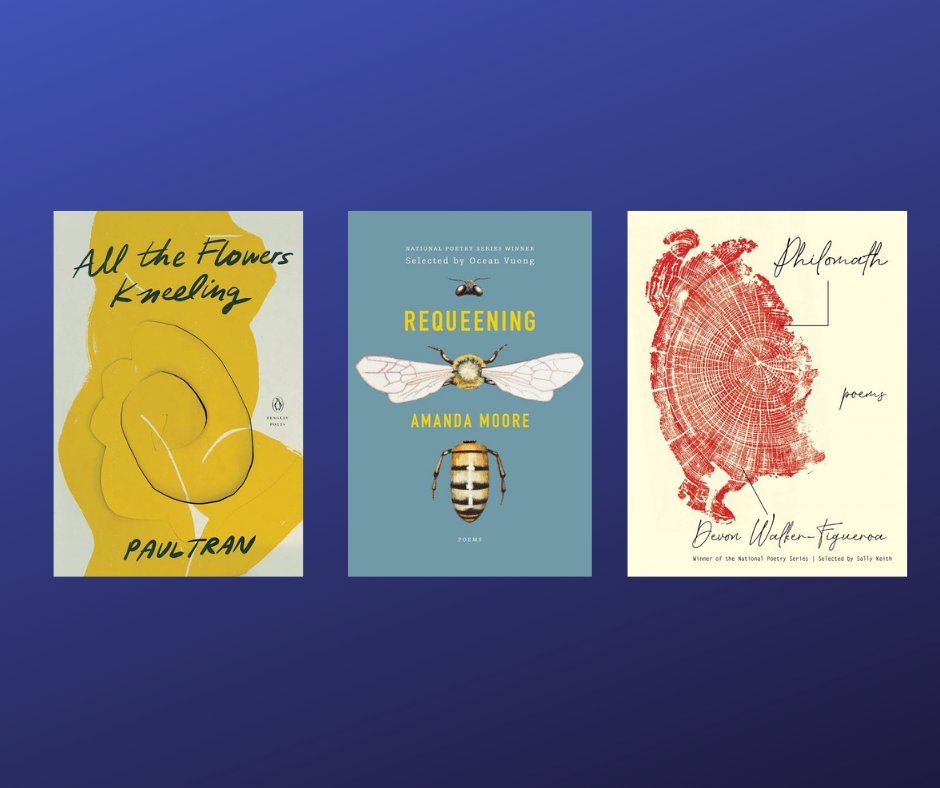

Four Takes: Devon Walker-Figueroa’s Philomath, edited by Corey Van Landingham, West Branch 101, Winter 2023

Review: “Excavating Personal Geography in Philomath,” by Mandana Chaffa, for Chicago Review of Books

A Freeing Space: Our Seventeenth Annual Look at Debut Poets

Excerpt from Poets & Writers - Jan/Feb 2022

How it began: A place, a people, a state of mind, a set of experiences that haunted me.

Another way to say it: I never set out to write a book called Philomath. The first lines of what would become the book took shape in a candlelit basement in Salem, Oregon, where I was bartending at the time. I’d scribble lines of poetry on guest checks and either stuff them in my apron or under the register drawer until my shift ended.

What would become the title poem of the book came along a couple of years later in response to an undergraduate poetry assignment given by Michael Dumanis at Bennington College. Michael had lit a fire under my heels and given me a new sense of the poetic line by introducing me to poets such as Shane McCrae, Samuel Amadon, Olena Kalytiak Davis, C. D. Wright, Kiki Petrosino, and Lucie Brock-Broido. With their voices fresh in my ears, I set out to write a poem that captured something of the essence of a world I’d passed through, or which had passed through me and left significant traces of itself. I called “Philomath” my “hometown poem.” And I’d go back and write more poems in this mode during my grad years at Iowa and a couple of years beyond.

The rest was just longing—to hold on to and preserve what’s receding from my consciousness; to connect with others in ways I can’t seem to when I’m physically in their presence; to estrange myself from what I “know”—and regret, which is also just a form of longing, I suppose, for the past to be other than it is.

Inspiration: A single-wide mobile home decorated with painted saw blades. Russian ballet teachers and Oregonian loggers. Harpists and cowboys and Gloucester’s leap. Vacation Bible School. Microwave dinners and ghost hunters. Lorenzo Ghiberti’s bronze reliefs on the Baptistery doors in Florence. An illuminated tank at the Oregon Coast Aquarium that’s full of moon jellyfish in their medusa phase. Loitering in art museums and used bookstores. A Season in Hell and The Divine Comedy. György Ligeti’s Atmosphères. Also, the voices of so many different people. I was a bartender for a number of years, so I got to hear a lot of tongues wag—that was a gift. Such blues and gossip and intoxicated babble. Those voices, their stories and syntactical tics and slang, they stick in my head until I metabolize them and then they find some phantom presence in a poem, the way everything we eat, in its way, becomes a tiny part of us, a bit of ATP flitting through the bloodstream, though we don’t see it happen. Which is to say, inspiration might be inevitable and often occurs when we aren’t looking or don’t yet feel it animating us.

Influences: Jorie Graham’s poetry found me at a crucial moment in my life, and my admiration of her swift and breathless movement and fearless images, which also often double as portals through time and space, has never faltered. The hypnotic abundance and onrushing music of Nathaniel Mackey’s “Mu” and “Song of the Andoumboulou” poems helped me to stop imposing so many arbitrary limits on my poems and enabled me to listen more closely to the poem as it was taking shape, to sense where the lines, and not just I, wanted to go. Lucie Brock-Broido’s daring and polytonal sense of line, intimacy of address, and elastic diction that reaches back in time and deep into the present moment all at once, was life-changing for me as well. The ballet and modern dancer Sylvie Guillem has greatly influenced my work, too, not just in terms of what I strove for in ballet, when that was my profession, but how I now approach sculpting the human form and moving through language on a page. Her versatility is astonishing, her ability to shift seamlessly from machine-centric to animal-centric movement styles and to evoke the ethereal and the earthen in a single step, not to mention her balance, surreal flexibility, and breathtaking lines—all of which continue to enrapture me and shape how I move through and with art.

Writer’s block remedy: I’m a big fan of denial when it comes to “writer’s block” or “burnout.” I like mostly to pretend it’s a made-up thing. But for the moments when my head is overcrowded with data to the point of being numb or I just can’t convince myself with my flat-earther approach to burnout, for the moments when I feel so far from the words as to be exiled from them, I try a two-pronged approach of returning to my roots—that is, the poetry I read that first led me to respond to it by writing poetry—and then simultaneously reaching far from my own sensibilities and seeking out works that challenge any aesthetic I might have settled into. The idea being this: Find the roots in order to move the roots, to transplant your writer’s mind, as it were, so you can draw from the strength you already have but also draw in new nutrients from soil you haven’t leached out with endless searching and absorbing and reabsorbing. To me, it’s all about the reading—whether what you’re reading is the page in front of you or the room in which you sit.

Advice: Don’t stop or pause your writing just because you’re trying to focus on getting your first book out there. The continuation and development of your creative process need not be disrupted by the apparent completion of a single work.

![[scroll down to bottom of site page]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/574645c7f8baf3649a5ebcb0/576505a5-614d-461b-98f1-7a3e801264b0/Screen+Shot+2021-11-23+at+3.29.09+PM.png)